Thomas Sharkey receives NSF grant to study isoprene emission from plants

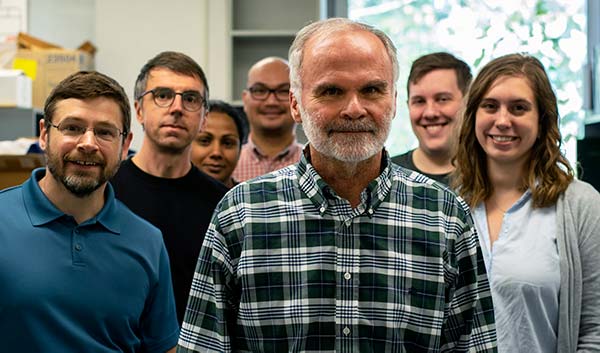

Building on years of breaktrough research, Michigan State University biochemist Thomas Sharkey has received a four-year, $898,946 grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to continue his research on isoprene emission from plants. The four-year grant will focus on the evolutionary pattern of the appearance and loss of isoprene emission among various land plants, and the impact of these emissions have on the atmosphere.

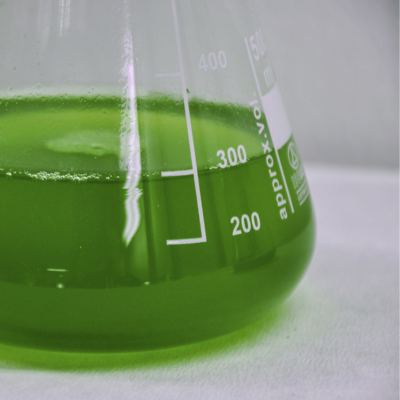

Isoprene is a gas molecule given off by many trees, ferns and mosses. The relatively frequent gain and loss of isoprene emissions and its scattered distribution among land plants indicates that the trait is constantly in an evolutionary balancing act, enhancing plant resilience and fitness, but at some cost to the plant. The question facing scientists is: What is it that triggers the coming and going of this trait?

Scientists are yet to fully understand the benefits plants get by making isoprene. What they know so far is that isoprene has been shown to enhance plant tolerance of heat, oxidative stress, and ward off insects that feed on them. Understanding isoprene emission in plants is important for determining if or when it might be useful to engineer crops to make it, or to engineer emitting plants to suppress it.

By Victor DiRita, Jr., MSU College of Natural Science

“We think the benefits and costs to plants of making isoprene are very nearly balanced,” said Sharkey, a University Distinguished Professor at the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory and member of the Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology at the College of Natural Sciences. “For some plants, the balance favors isoprene emission, while others are on the cost side of the tipping point. This work will give a much clearer picture of the cost-benefit balance and will help us understand this very important molecule.”

It is also critically important to understand these isoprene emissions because they are a major concern in atmospheric chemistry, contributing to tropospheric ozone formation (the bad ozone, precursor to smog), aerosols and formaldehyde, especially in atmospheres polluted with nitrogen oxide. Plants, particularly trees, emit significant amounts of isoprene into the atmosphere. Because of this, atmospheric modelers need to know how much isoprene is emitted from vegetation and how this may change in the future.

“We believe that a thorough understanding of the forces that shape the evolutionary history of isoprene emission from plants will improve future global emission estimates,” said Sharkey, who also serves as Associate Director with MSU’s Plant Resilience Institute.

The study has three primary aims: to investigate the benefits of isoprene emission, the costs of isoprene emission and the genetic mechanisms that isoprene may coopt to relgulate the rate of synthesis and resilience toward plant stress. The overall goal of the research is to determine which specific evolutionary constraints are responsible for selecting for maintenance of isoprene emission in plants and those that favor the loss of the trait.

By Igor Houwat, MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory

The scientists will focus on three plants. Two are non isoprene-producing plants, Arabidopsis thaliana and tobacco, that have been engineered to make isoprene. The third plant, poplar, makes a lot of isoprene, but has been engineered to stop making the molecule.

“Information gained from this study will enable us to understand receptors and pathways in plants that facilitate the signaling process of isoprene and how isoprene signaling ‘cross-talks’ with other well-known growth and stress-repsonsive signaling pathways,” Sharkey said. “Knowledge of the dominant evolutionary constraints and factors that enhance the likelihood of isoprene-forming enzymes will enable us to predict the evolutionary trend of isoprene emission in response to climate change.”

Research on isoprene is also of interest to the the biotech industry. A number of projects are aiming to convert it into a source of biofuels or industrial raw materials. New insights from the Sharkey lab could help bioengineer better sources of isoprene.

An important component of this research is the inclusion of students participating in the MSU Plant Genomics REU Program, which provides high quality research and training programs for underrepresented undergraduate students interested in biochemistry, bioinformatics, biology, biotechnology, chemistry and computational sciences. Several of these students have been involved in isoprene-related projects and have been co-authors on publications from Sharkey’s lab.

“This program is an excellent resource to inspire and train a future workforce that is diverse and globally competitive,” Sharkey said.

Another goal of the program is to improve public scientific literacy. Sharkey and his team will participate in MSU’s Fascination of Plants Day—a worldwide event that aims to enthuse the public about the importance of plant science in everyday– and the MSU Science Festival to share information on their research.

Banner image: Plants, particularly trees, emit significant amounts of isoprene into the atmosphere. The lab of Thomas Sharkey will study the evolutionary pattern of the appearance and loss of isoprene emission among various land plants and the impact these emissions have on the atmosphere. Image by Diliff, CC BY-SA 2.5.

By Igor Houwat, Val Osowski, Thomas D. Sharkey